The real world doesn’t always match the map. You’re confidently following your navigation app when suddenly a construction site blocks your way, or the sidewalk just ends.

For many people these moments go beyond an inconvenience, they affect safety and access to the world. For a wheelchair user, encountering an undropped curb or a broken elevator on a route marked as step-free can completely restrict their ability to reach their destination.

Having created the Inclusive Wayfinding Kit, an open set of tools and recommendations for inclusive wayfinding systems for active travel, we know that consistent data about pedestrian infrastructure not only helps establish trust between people and navigation tools, it builds people’s confidence to explore new places and move around their community. It unlocks more equitable, inclusive opportunities for individuals, benefiting society and the environment.

Discrepancies between the real world, and the world represented by navigation apps typically comes down to data. The reasons for these discrepancies can be nuanced. Data could be missing, outdated or not correctly recorded, but the result is clear: when consistent, useful information is missing, we lose trust.

Consistency and completeness of datasets is only part of the story. The structure of this data is critical. Data structure and standards answer questions like:

- How should real-world infrastructure be represented or logged as data points?

- What attributes should be standard when describing a path?

- What units are associated with the data attributes?

Right now, these pedestrian data standards are being defined. It’s a conversation worth paying attention to and being a part of.

What’s happening in the world of pedestrian data.

In recent years, the geospatial data community has initiated three important projects with the aim of improving datasets that underpin the pedestrian experience. Scale and standardization are critical conditions for this data being useful. We need cross-sector collaboration to establish how we collect data and define standards. Three leading projects are being driven by geospatial data communities in the United States.

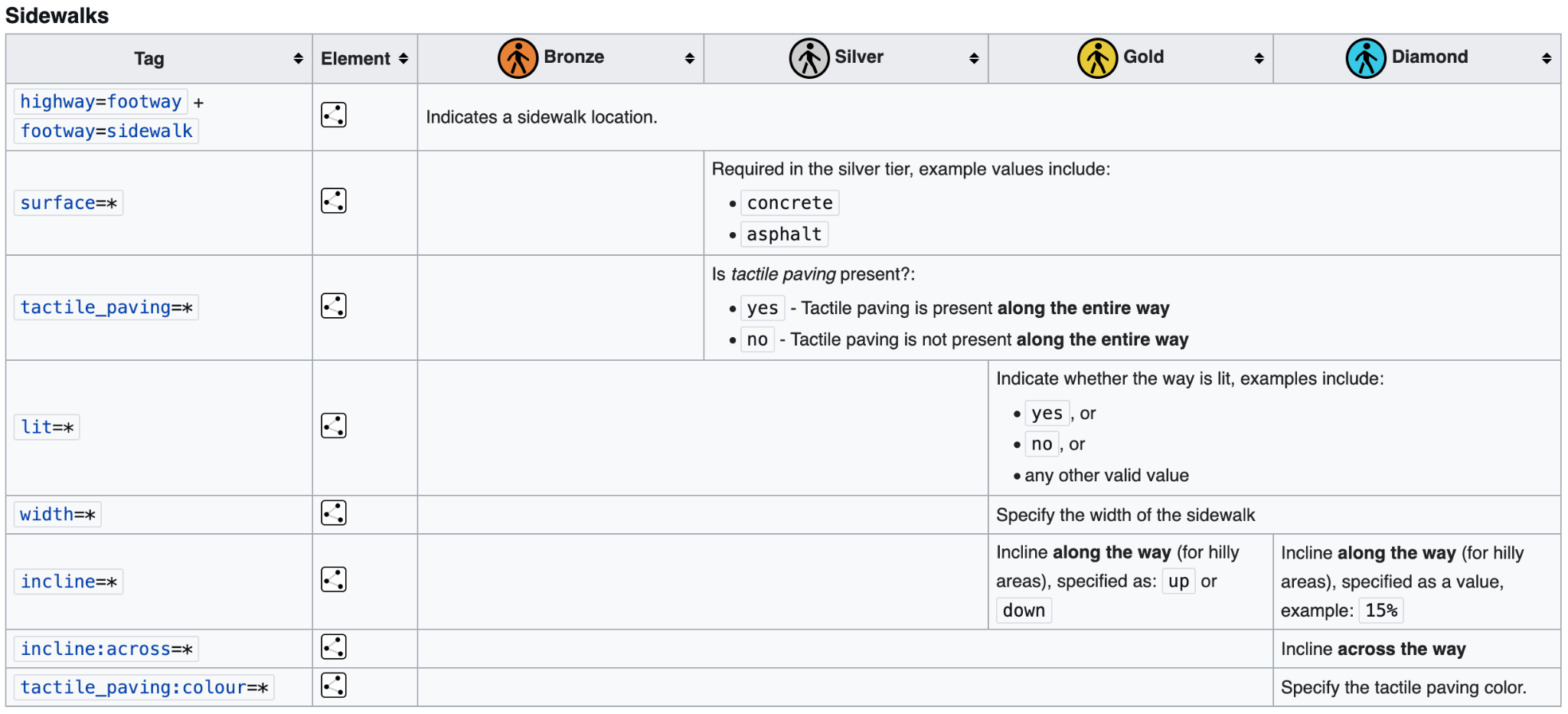

The first project is an OpenStreetMap (OSM) community initiative led by the fantastic volunteers of the US Pedestrian Working Group. This Working Group has developed a multi-tiered guideline to improve how sidewalks, crossings, connectors, curbs, and other infrastructure are recorded in OpenStreetMap. It serves as a practical “start here” guide for mappers, helping more people get involved creating wide coverage and consistent standards.

The second is the US National Collaboration on Bicycle, Pedestrian, and Accessibility Infrastructure Data (NC-BPAID) and the release of their draft specification: General Active Transportation Infrastructure Specification (GATIS). This specification is the result of more than a year of stakeholder engagement, research and coalition building. The objective of this initiative is to develop a shared data specification that can be used across the US, “to enable data sharing and coordination at a national scale.” Data producers could include local municipalities, local transportation agencies, or even private-sector data producers who want their products to be compatible with other public datasets. For agencies that are preparing active travel infrastructure data for the first time, GATIS provides a roadmap for how to go about collecting data.

The third is OpenSidewalks, developed by The Taskar Center for Accessible Technology at the University of Washington. While the first two projects I mentioned have many benefits for users with accessibility needs, the core mission of the OpenSidewalks project is to develop “a comprehensive and accessibility-forward specification for mapping sidewalks.” It focuses exclusively on the pedestrian experience, collecting detailed data that is crucial for wheelchair users and others with accessibility needs. This includes attributes like width, surface composition, steepness and whether the path is shared with traffic.

Why now?

Better coverage, quality, precision and consistency of data will improve the experience of people travelling around by walking and wheeling. The good news is the cost and speed of collecting pedestrian infrastructure data is reducing, while interest in the area has become more widespread.

Reasons for this:

1. Geospatial data is no longer niche, the world is largely mapped, and we have moved the goal-posts. Google Maps, the most used mapping application, is 20 years old and used by one billion users each month. OpenStreetMap, at 21 years old, is also integral to our contemporary digital world. More than 80% of the world’s road networks have been mapped in OSM. With a significant portion of the world’s foundational infrastructure now mapped, map users expect more detailed features, like pedestrian infrastructure.

2. Cities and transit agencies are more data savvy than ever before. Compared with ten, or even five, years ago, cities and transit agencies have stronger in-house capacity to create, publish and govern data.

3. The demand for more detailed data by myriad data-hungry apps means the private sector is investing in collecting this information. Large, private sector companies employ mappers to add features to OSM. Meta, for example, invests in ‘Organized Editing’ programs, like “The Walkabout - Pedestrian Mapping Initiative." The objective of these programs is to improve pedestrian data for the use in products and services. These are the maps that get used in Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp – mass consumer facing products that use geographic context to inform social interactions.

4. AI is driving down the cost of data acquisition. Traditional methods to collect pedestrian infrastructure data often required costly surveys and audits.1 Today, there are multiple computer vision tools and services that can collect information about pedestrian infrastructure at scale, rapidly, and relatively cheaply. From new platforms like Hivemapper, which has developed a cheaper device to collect imagery about road infrastructure, to re-purposing CCTV feeds to classify city infrastructure. It is easier than ever before to capture exceptionally granular data.

From digital representation to real world experience

While data schema development doesn’t sound as glamorous, or attract the kind of hype that other technology innovation commands, such as AI, it is the silent driver of our pedestrian experience. From the digital routing applications that we use to plan our journeys, to prioritizing where to invest in placemaking, wayfinding and pedestrian safety infrastructure – digital representations of our world inform real world decisions.

Data standards and collection might sound mundane, but its impacts are anything but. When we have comprehensive coverage of information about the status and condition of sidewalks, curbs, crossings and other pedestrian infrastructure we can respond to the elements that most impact pedestrian safety and people’s willingness to walk.2

Getting involved

How we define, talk about, measure, represent and prioritize pedestrian infrastructure is taking form now. As this develops, schemas and standards will become more established and changing them will become a slower process. Now is the time to get involved.

If you work in placemaking, transportation, accessibility or masterplanning, participate and contribute your knowledge to the pedestrian data revolution. If you ever walk, wheel, cycle or take public transportation, share what is meaningful or affects your experience with the active initiatives described above. Your voice should be heard and considered as we test early ideas and blueprints for describing and defining important features of the pedestrian experience.

You can comment in the GATIS draft schema document. You can join an OSM Pedestrian Working Group Meeting. You contribute directly to OSM. If you work for an organisation that collects or handles this data, understand how you might align current data management efforts with these broader initiatives.

And, talk to us. We work with pedestrian data every day. I would be delighted to have a conversation with you about how to make the most of pedestrian data in your work.